Cassils walked into the dance studio, stepped into the middle of the Marley floor, and surveyed the vaulted space quietly. I remembered the day, five months ago, when the LAP visual arts jury watched the riveting video of this artist being set on fire, and scrolled through images of performance art built on body-building, physical endurance, and a liminal bodily presence. I had not expected such gentleness. Cassils looked around the studio as the robins chirped in the oak trees outside.

“Is there a bigger space anywhere at Montalvo? We’re choreographing a fight scene in a parking lot.”

And thus began our search for the perfect space for a fight. Choreographer Mark Steger was arriving in a few days to work with Cassils on their latest performance piece, The Powers That Be , which would premier at The Broad in about two weeks. We needed the space pronto.

|

ABOVE: Cassils and Steger rehearse in West Valley’s wrestling room. Photo credit: Lori Wood.

|

The area needed to be twenty by twenty feet, the size of the performance space in The Broad’s parking garage, where Cassils would perform the work to a soundtrack composed by their collaborator, artist Kadet Kuhne . The padded mats the artist had ordered could not be delivered in time, so the space also needed to be padded. Research and brainstorming ensued, including Cassils’s last-ditch idea of taking every futon in the LAP and spreading them over the Villa ballroom. At 3 pm on a Friday and with Mark Steger on his way, we threw ourselves on the mercy of West Valley College, and by Monday, Dean Brad Weisberg had cleared the way for Cassils to use the gloriously padded wrestling room PE11—the perfect space for a fight.

|

Cassils’s new performance piece, The Powers That Be , grew from a performance the artist created in 2014 while in Kuopio, Finland, where the artist was in residence as the first recipient of the ANTI International Prize for Live Art. Situated just 210 kilometers from the Russian border, Kuopio could pick up Russian radio signals. It was the time of the 2014 Olympic Games, when Olympic athletes’ protest against the ongoing treatment of LGBT people in Russia made the issue of anti-LGBT violence more widely known.

Over artists’ dinner by the fireplace in the LAP Commons, after a strenuous day of rehearsals, Cassils described the genesis of The Powers That Be as a reflection on the ongoing violence toward LGBT people perpetrated by the Russian vigilante group, “Occupy Pedophilia.” This violent group, which claims to target pedophiles, lures gay people to “dates” through online dating sites. The victim, once entrapped, is confronted by a group of anti-gay individuals who torture and humiliate them. The attack is videoed and posted on the internet, outing the victim in a country where it is illegal even to discuss gay issues between parent and child. Cassils spoke about the chilling experience of watching these internet videos as research for the initial performance piece in Kuopio.

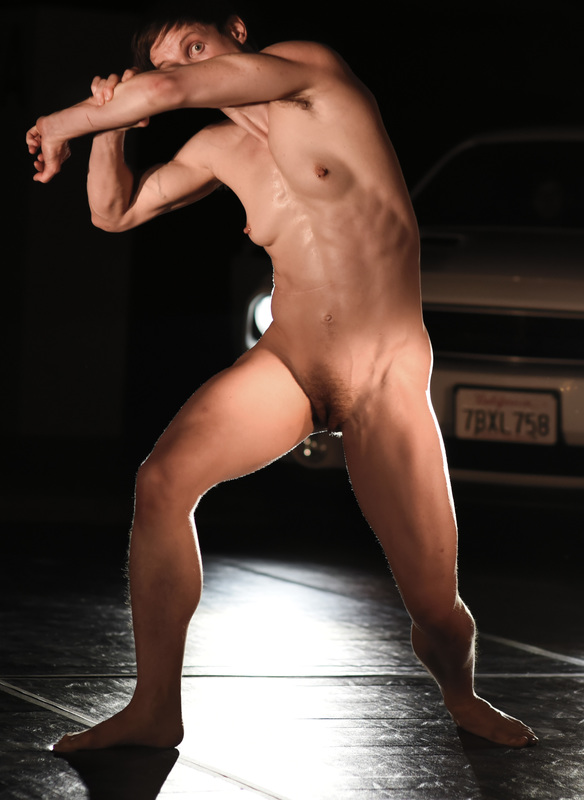

The Powers That Be is a performance that enacts the stark experience of a single body attacked and attacking an invisible other in a bare space. The unforgiving cold of a garage is the scene of struggle, lit only by car headlights. The setting is like a bad dream, the victim alone and with no hope of aid. It is a one-person fight scene without a moment of submission. The victim is going to fight it out or be throttled trying. The perpetrator is there too, flickering up and out of a single body, rolling onto an invisible victim and holding them in a headlock. There is the sound of human breath in struggle, and a soundtrack by Kadet Kuhne incorporating radio scans through static, human voices arguing the controversies of our times, punctuated by advertising. There will be an audience watching and not intervening. They will have to bear that. And they will be invited to film the attack on their cell phones. The brave ones will do this. Some won’t, and in this way may hope to be absolved of watching. But we are all implicated, and they will know it.

I sit at the edge of PE11 and watch Cassils rehearse the piece with choreographer Mark Steger. There is the smack of skin on skin and the sound of ragged breathing. It is not always clear when the switch has come, who Cassils is inhabiting now as their compact, muscled body hits the mat and rolls. Held breath, muscular strain. There is an intimacy to this violence. Cassils is being attacked. Cassils is attacking. I have the sense that the artist is traveling deep into experience to see what can be found there and bring it back up into the light. The search tool here is the body at the furthest point of exertion. It falls to us to watch. (But we like watching, don’t we? It’s how we live now.)

Then suddenly it is as if someone has flicked time’s switch and the action slows. Cassils’s arm follows a tight, slow arc and we experience that Hollywood slow-mo effect that evokes the glory of violence. We hold our breath and wait to see if we are transported to the glory. The switch is flicked again and fist meets absent victim’s face. Or is it the perpetrator who is knocked back for once? Is the victim gaining ground? Cassils gasps and writhes.

Cassils inhabits liminal spaces and enacts them. This one is on both sides of that threshold of perpetrator and victim, but also the threshold between subject and object: Cassils the artist offers Cassils in extremis to our gaze. But this breathing is too intimate. I am extremely conscious of my gaze. My manners tell me, this is a private moment of pain. I should look away. Cassils’s work says, watch me .

Performance artist Marina Abramovic said, “What I’m doing is inventing events that I am afraid of. I go in front of the public and, if I can do it, they can do it, too. That’s why performance art—if it’s good—can be a life-changing experience.” In Cassils’ work, Inextinguishable Fire (2007-2015), the artist used their own body, set aflame, in an artistic enactment that engages the limits of bodily endurance, as well as the limits of witness and empathy.

|

ABOVE: The Powers That Be , The Broad Museum, April 2016. Photo credit: Cassils with Leon Mostovoy. Photo courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts.

|

Cassils’s work is informed by, and has responded to, a long history of feminist performance art that has animated questions of objectivity and subjectivity, from Abramovic’s performances that willfully subjected her body to pain and danger, to Valie Export’s art that examined the power relations inherent in media representations of women’s bodies. Cassils has taken this exploration further, to turn this lens on representations of trans bodies, and to dramatize the agency of self-construction. In a succession of poetic and striking public performances, Cassils has dramatized the discipline and endurance required to remain in that liminal space between what we assume to be two poles of gender, dramatizing the tensions involved in both performing the ordeal of gender, and of watching that ordeal. The artist is giving us a lesson in how to make ourselves, and how much work that entails.

|