Among the featured artists is Mexico-born Hector Dionicio Mendoza, currently based in Monterey, California. Mendoza’s mixed media practice, which includes sculpture and two-dimensional works, often combining the organic and the man-made and exploring a wide range of themes, including the everyday potentiality of catastrophe.

In this short video created by filmmakers Alexis Costanza and Pierce Leggin, Mendoza gives us a unique view into his working process as he describes how he created a new series of works on paper for Botanica Poetica, White Wilderness, while he was an Artist Fellow at the Lucas Artists Residency Program.

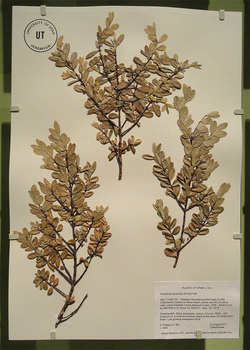

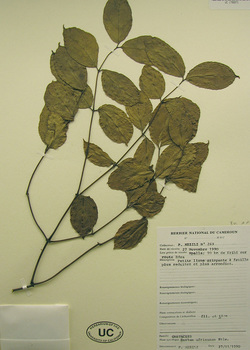

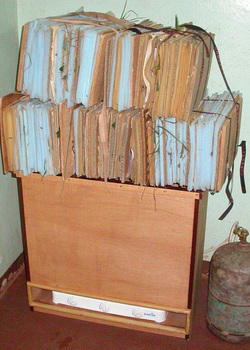

As is true for many of the artists whose work is featured in Botanica Poetica , Mendoza ’ s creative approach recalls some of the standard methods used in botanical research. He mimics and appropriates the methodology of the herbarium – a collection of preserved plant specimens typically found in universities, natural history museums, and botanical gardens. Essential for the study of plant taxonomy, h erbarium specimens are usually dried and pressed plants affixed to a sheet of cartridge or other archival quality paper, with information indicating provenance and identity.

|

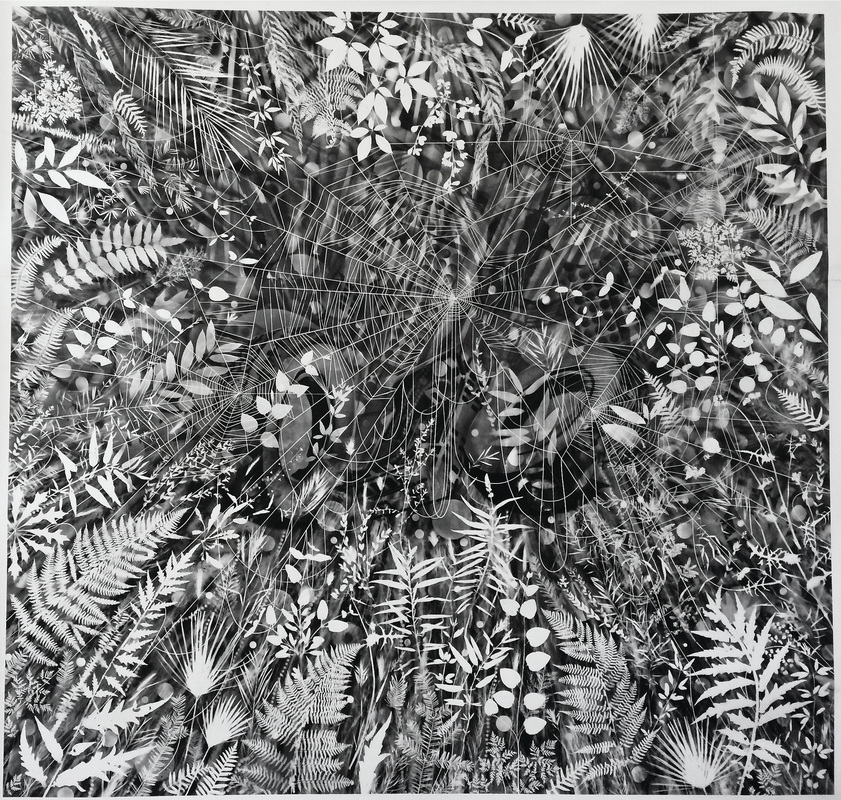

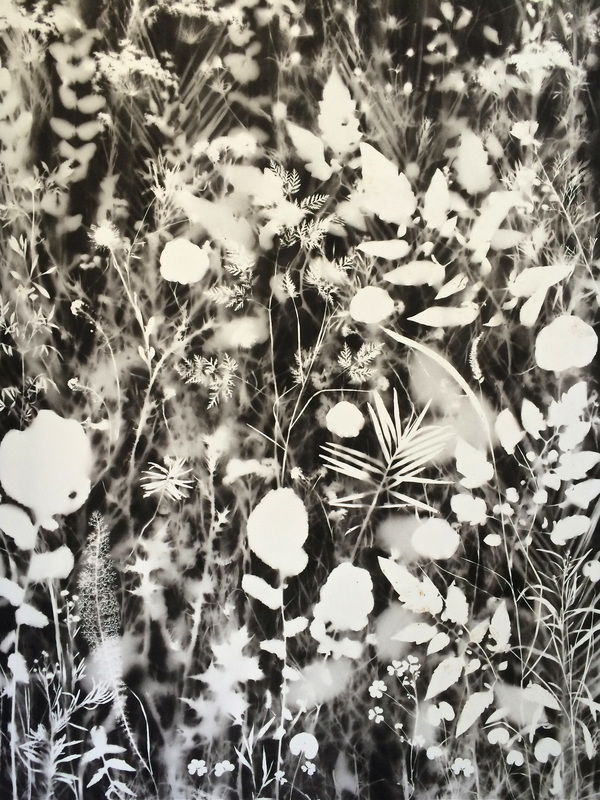

But then Mendoza does something surprising – he turns this botany-inspired process on its head by introducing a medium more closely associated with urban life and the street art form graffiti: spray paint. Using his plant specimens like a reversed stencil template, the artist applies black aerosol paint to create two-toned black and white images. Layers of flora samples create the illusion of depth–the sharp silhouettes of plant life situated closest to the paper surface contrasts with the less defined details of subsequent foliage overlays. The resulting images resemble the photogram cyanotypes of English botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (1799-1871), especially her cyanotypes of ferns from the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

|

All spiders are predatory and nearly all are venomous. Most weave a deadly trap in the form of a web. Despite its great beauty, for Mendoza the backcountry is also a space of potential threat and danger. In the tradition of John Muir and Henry David Theroux, descriptions of ‘ wilderness ’ often take the form of ahistorical pastoral fantasies coded as ‘ white, ’ and often overlook the complex historical relationships between wilderness and people of color. As an example, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the spread of lynching in the 20th century transformed the forest wilderness into a fearful place for many African Americans. In Mendoza’s White Wilderness No. 5 , beyond the spider’s web are the shadowy shapes of two tires. In recent years, the Mexican countryside has become the backdrop for drug-related kidnapping and murder, mass graves, and ultraviolence, including necklacing–the appalling method of killing a victim by putting a petrol-filled tire around his or her neck and setting it on fire.

The tires on view in White Wilderness No. 5 also recall the urban Mexican American experience of car customization and Lowriding. They are out of place in this wilderness setting–a reference to the lack of minorities in America’s national parks, where visitors continue to be predominately non-Hispanic Caucasians.

|

Back to the spray paint, because materials matter. Often associated with expressions of anti-establishment sentiment the storied history of modern graffiti is intertwined with the punk rock movements of the 1970s, and Hip Hop and Chicano culture of the late 1970s and 80s. Mendoza ’ s black spray paint points to an earlier moment in graffiti history. West Coast Mexican American “ zoot suiters ” of the 1930s and 40s began creating placas , a distinct calligraphic tag that they applied to urban spaces as an affirmation of identity. Later in the 1960s and 70s placas were adopted by Latino gang culture and used to mark and delineate territorial street boundaries. Often painted at the edge of a neighborhood, placas included the names of a gang and its members, and they were almost always painted in black letters.

|

IMAGE KEY

Image 1 : Garrett Herbarium specimen exhibited in the Natural History Museum of Utah , Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. By Daderot (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons. [ Back to image ]

Image 2 : Gnetum africanum, UC specimen 1782271, collected 27 November 1990, P. Mezili no. 269 Mpalla, 10 km de Krib, EncycloPetey (Own work) [GFDL ( http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html ) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0) ], via Wikimedia Commons. [ Back to image ]

Image 3 : Drying herbarium specimens with a gas cooker and a wooden construction. Design of the Herbier de l’Université de Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. By Marco Schmidt [1] (Own work (own foto)) [CC BY-SA 2.5 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5) ], via Wikimedia Commons. [ Back to image ]

Image 4 : Anna Atkins, 1848/59, canotype, 9.88 x 13.88 inches. Minneapolis Institute of Arts . Anna Atkins [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. [ Back to image ]

Image 5 : Hector Dionicio Mendoza, White Wilderness 5 , 96 x 96 inches, spray paint on paper, 2015. [ Back to image ]

Image 6 Hector Dionicio Mendoza, White Wilderness 6 , 30 x 40 inches, spray paint on paper, 2015. [ Back to image ]

Image 7 : Howard Gribble, Photo of Sunset Boulevard in LA, c. 1970. All photos copyright and via Howard Gribble . [ Back to image ]