This coming Sunday, December 6, Oakland-based artist

Monica Lundy will join companion Lucas Artist Fellows

Kija Lucas and

Fieldworks (Trena Noval and Ann Wettrich) for a conversation about their new nature themed work currently on view in Montalvo’s gallery exhibition,

Botanica Poetica . This short video (click above to view), created by local filmmakers Alexis Costanza and Pierce Leggin, depicts Lundy in her studio at the Lucas Artists Program discussing her work and creative process.

Lundy’s multimedia works often develop from her archival research into lesser known histories of marginalized communities. In 2009, she began a series of gouache on paper portraits based on photographs she discovered in the California State Archives of female inmates at San Quentin State Prison. A compelling cache of mug shots of women arrested for prostitution in the mid-1900s–which Lundy encountered in the San Francisco Public Library’s Historic Photograph Collection in 2012–formed the basis of an arresting series of portraits created using pulverized charcoal, mica flake, coffee, ink, gouache, acrylic, and acrylic gel on paper. In search of new inspiration, Lundy has just returned from a research trip to the UK where she spent time exploring the long and storied history of London’s psychiatric asylums, and visited the archives of Bethlem Royal Hospital (also known as Bedlam) and the Welcome Library’s Holloway Sanatorium Hospital Collection.

The botanical theme of Lundy’s newest body of work, created while she was a Fellow at the Lucas Artists Program, seems at first glance to be a radical departure for the artist. Indeed, the artist has talked at length about how exchanging her normal studio space in urban Oakland for the natural setting of Montalvo served as a creative stimulus (hoping to share this experience with her fellow artists she organized

a pop art plein air day at Montalvo and founded a new art group:

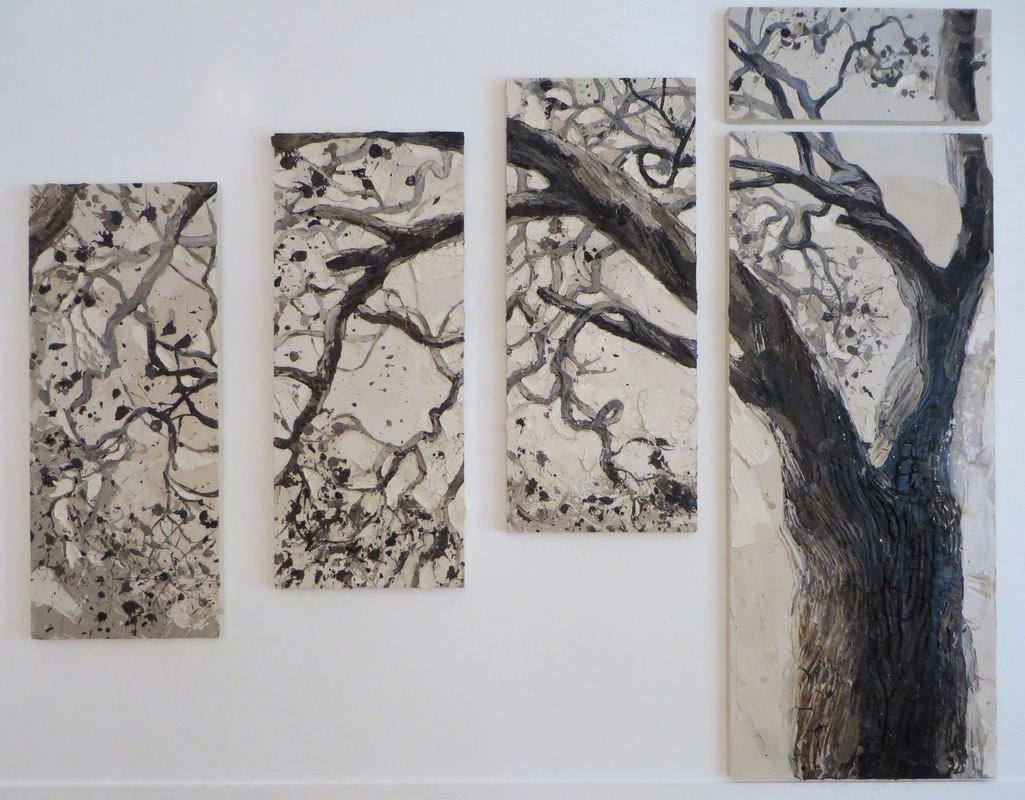

the Art Escapists ). An important continuous thread in Lundy’s work, however, is her use of unconventional materials: she has used such diverse media as coffee, white and yellow gold, green tea, rusted cut steel, clay, and porcelain slip to create densely viscous surfaces that blur the boundaries between painting and sculpture. With her new large-scale multi-panel portrait of a Valley Oak (

Quercus lobata ), she continues this experimental approach by creating a new painting medium–a mix of clay, pigment, and adhesive. The result is a thick textured and cracked surface that captures the tactile quality of oak tree bark. Lundy’s risk-taking led to some happy accidents, such as the stunning burnt brown color on the trunk–the outcome of a smoldering unstable amalgamation of clay, pigment, and adhesive. Quieter passages of white, dappled impressionistic leaves, and twisted branches rendered by hand combine to capture the essence of this majestic old tree.

|

|

The kinship between Lundy’s botanical themed portrait and earlier works based on archival sources extends beyond her unusual use of materials. In the video interview above, Lundy describes how she sees the oak tree “as a living history […] some of the oldest history we have in California.” Every Californian school child learns about the oak when they study the history of the US’s First Nations peoples. All subsistence, pre-agricultural economies relied on acorns from oak trees, but Native Californians are the only remaining example of a balanoculture–a society for which acorns were a staple foodstuff. As Jared Farmer in his 2012 book Trees in Paradise points out “To this day, the sight of a gnarled oak on a brown hillside suggests indigenousness, permanence, and belonging.”

|

This is in contrast to non natives like the ubiquitous eucalyptus tree, which has become an ambiguous symbol of Californianess–loved for its menthol odor by some and despised by many as water guzzling ‘alien.’

But the oak tree is also a register for other kinds of human histories. Hominids “became human beings as they learned to use oak.”Settlers and immigrants in the US made ink from oak galls and built furniture, homes, and ships from oak lumber. Then came the lumber barons and urban developers, and with them massive deforesting projects. Oakland’s beautiful oak woodlands made way for new homes in the early 1900s. Saratoga was home to a thriving lumber industry in the mid-1800s fueled mostly by its abundant redwood forests. Archival photographs from the early 1900s held at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, depict a much sparser Montalvo than we see today. Politician, business man, and Montalvo’s original owner, James Duval Phelan began replanting redwood and oak trees to beautify his summer home as early as 1912.

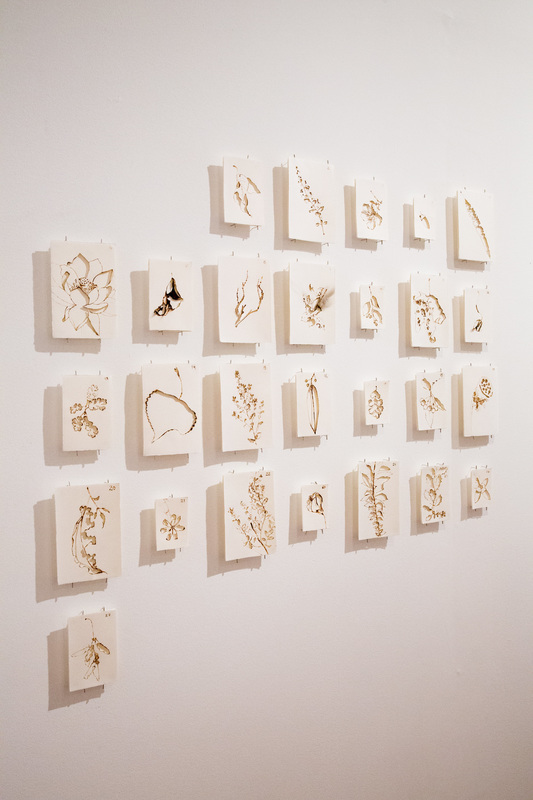

Today, the oak tree registers the environmental impacts of human driven climate change– a warming climate has made the invasive pathogen that causes Sudden Oak Death harder to control; sprawling development into woodland areas combined with lack of precipitation and soaring temperature have led to the growing intensity and regularity of large-scale forest fires throughout the US. Lundy underlines the dangers of our warming world with her series of burnt drawings in which she depicts poison oak plants and other botanicals using a soldering iron.

From symbiotic to disharmonious, more than any other plant species, the oak tree chronicles humankind’s evolving relationship to the natural environment. Portrait of an Oak Tree , like Lundy’s portraits of female inmates from the 1900s, is a hidden history–one which the artist has brought out of the shadows through with her powerful expressive depiction of the tenacious Quercus .

IMAGE KEY

Image 1 : Monica Lundy, 13793 , 2011, gouache on paper, 30 x 22 inches. Courtesy of the artist.[ Back to image ]

Image 2 : Monica Lundy, 0-3640 , 2012, pulverized charcoal, mica flake, coffee, ink, gouache, acrylic and acrylic gel medium on Fabriano paper, 80 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist. [ Back to image ]

Image 3 : Monica Lundy, Portrait of an Oak Tree , 2015. Mixed media with clay on panels, 128 x 154 inches. Courtesy of the artist. [ Back to image ]

Image 4 : Kija Lucas, In Search of Home, Bay Area, 419, Eucalyptus , 2015, Archival Pigment Print, 40 x 30 inches (unframed). Edition 1 of 5. Courtesy of the artist. [ Back to image ]

Image 5 : [View of vineyards and estate], James D. Phelan Photograph Albums, Volume 96, 132. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. [ Back to image ]

Images 6 & 7 : Monica Lundy, Botanical Calendar (burned): September 2015 , Burned drawing on Fabriano paper, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist. [ Back to image ]

ARTICLE BY DONNA CONWELL