By Emily K. Holmes for Art Practical

Originally published February 17, 2018

Five days before the one-year anniversary of President Trump’s inauguration, I visited the artist Laurie Anderson during her residency at Montalvo Arts Center in Saratoga, California. We sat at a long wooden table in the residents’ airy, light-filled communal dining room while Anderson’s laundry whirred in the next room. Over the course of thirty minutes, our conversation strayed from the artist’s new book (released by Rizzoli this month) to her deep concern for the current political moment. Along the way, our talk touched upon language, narrative, and memory, themes that infuse Anderson’s broad-sweeping creative practice.

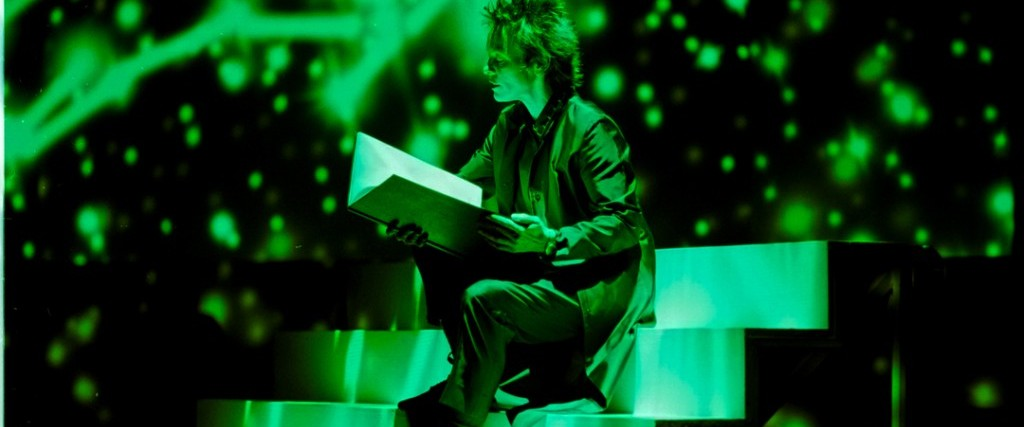

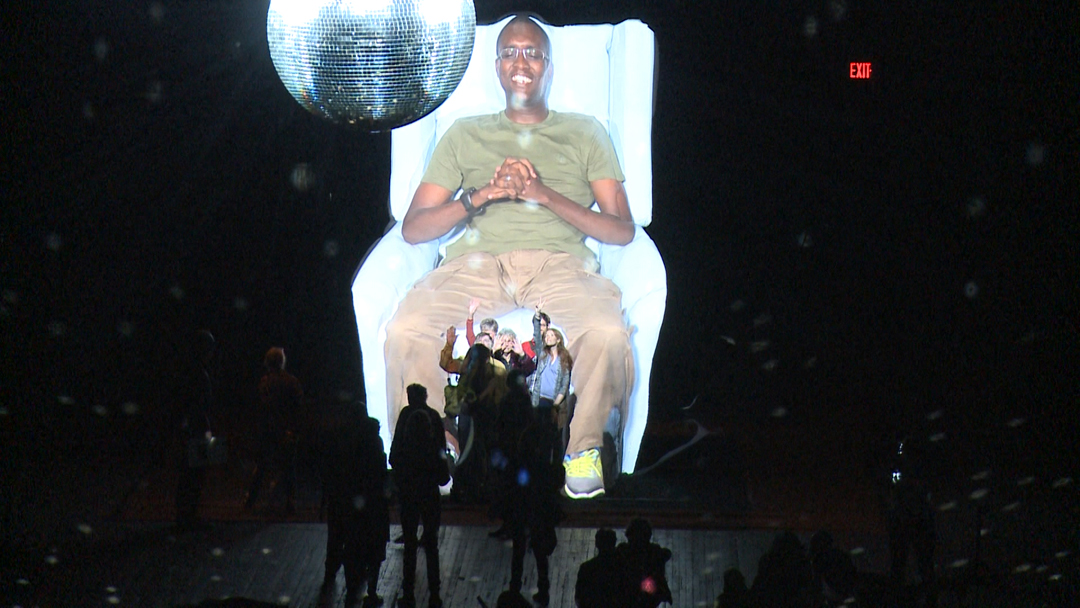

Anderson is a prolific artist, and one whose practice is remarkably interdisciplinary. If a viewer saw an early Anderson piece, they might have experienced an eight-hour performance of United States (1983) with the artist onstage switching between violin, uniquely designed musical instruments, spoken or sung lyrics, and projected images. [1] In 1980, one might have turned on the radio and heard “O Superman,” which became a high-ranking single on the British charts.[ 2] More recently, New Yorkers might have visited Habeas Corpus (2015) at the Park Avenue Armory, an installation that featured an enormous, live-streamed projection of previous Guantánamo Bay prisoner Mohammed el Gharani.[ 3] One year later, residents of the same city were treated to an Anderson concert composed and performed entirely for dogs (human guests were welcome to join).[ 4] And, currently in Taiwan, visitors to Anderson’s exhibition La Camera Insabbiata (also called Chalkroom ) (2017) at Taipei Fine Arts Museum don virtual-reality headgear to explore the artist’s collaboration with Hsin-Chien Huang in a dreamlike simulation of flight.

Anderson is a prolific artist, and one whose practice is remarkably interdisciplinary. If a viewer saw an early Anderson piece, they might have experienced an eight-hour performance of United States (1983) with the artist onstage switching between violin, uniquely designed musical instruments, spoken or sung lyrics, and projected images. [1] In 1980, one might have turned on the radio and heard “O Superman,” which became a high-ranking single on the British charts.[ 2] More recently, New Yorkers might have visited Habeas Corpus (2015) at the Park Avenue Armory, an installation that featured an enormous, live-streamed projection of previous Guantánamo Bay prisoner Mohammed el Gharani.[ 3] One year later, residents of the same city were treated to an Anderson concert composed and performed entirely for dogs (human guests were welcome to join).[ 4] And, currently in Taiwan, visitors to Anderson’s exhibition La Camera Insabbiata (also called Chalkroom ) (2017) at Taipei Fine Arts Museum don virtual-reality headgear to explore the artist’s collaboration with Hsin-Chien Huang in a dreamlike simulation of flight.

When considering the expansiveness of Anderson’s artistic practice, an adjective like “interdisciplinary” starts to seem like an understatement. In fact, her body of work and choices of media might seem all over the place. Themes do emerge, though, like language, memory, loss, power, and authority. Even when working with abstract or philosophical topics, Anderson’s works are anchored in the personal. When I asked how she chooses a new topic for her artworks, Anderson explained, “[I look for] something that I can personally get involved in, and not just be intellectually involved in: I can meet somebody in that world, I can go there, that I can try to express it in another way, perhaps. Articulate it.”[ 5] In doing so, Anderson pinpoints the humanity of topics that risk depersonalization, particularly political topics that some lawmakers and politicians might prefer to remain emotionally disconnected in the public eye. In the overtly political Habeas Corpus , Anderson’s decision to find a person “in that world” of Guantánamo Bay and to project el Gharani’s body in real time, a process she described as collaborative, put a literal face on the issue of detainees.[ 6]

Laurie Anderson. Habeas Corpus , 2015; installation view. Courtesy of Rizzoli.

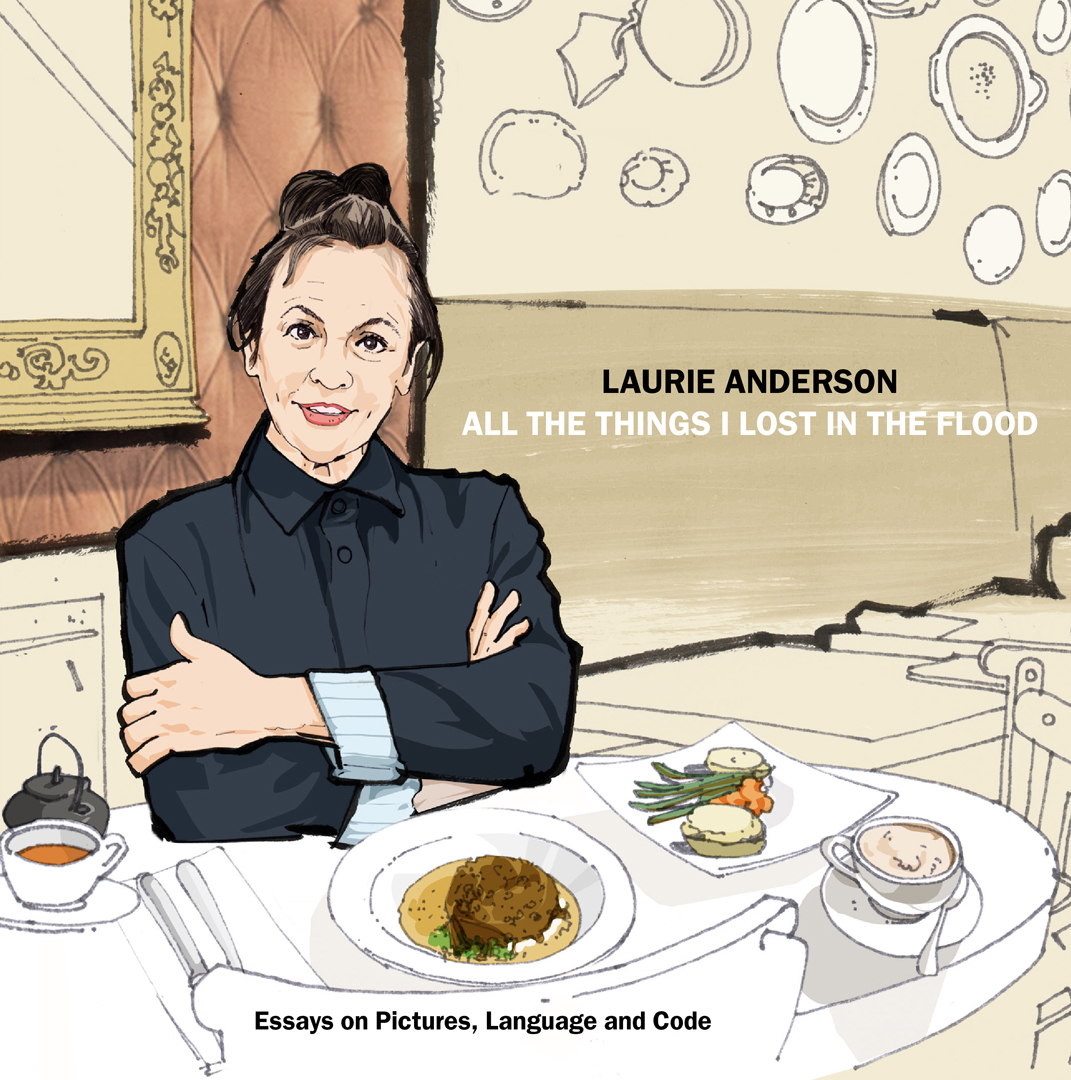

In other instances, Anderson digs into her own emotional experiences to get at larger issues; 2015’s feature-length film Heart of a Dog revealed Anderson in pensive contemplation of love, grief, and death as related to her own relationships with a beloved pet rat terrier, friends, and her late husband, musician Lou Reed. More recently, Anderson pored through her extensive personal archives—spanning four decades of work—to author a new book, All the Things I Lost in the Flood: Essays on Pictures, Language, and Code (Rizzoli, 2018). Billed on the publisher’s website as “the most comprehensive collection of her work to date,” the book isn’t just a survey. “It’s really about how stories relate to imagery, whether it’s film or sculpture,” Anderson explained. Like her visual and musical work, the publication encompasses both personal experiences and much broader topics. The title refers to the impact Hurricane Sandy had on Anderson’s home in New York, and her subsequent reaction to the experience. After the 2012 flood, Anderson had hoped to salvage some possessions in her basement, but she found only disintegrated objects. Even electronics and furniture were destroyed. “I looked at this floating pulp and thought, whoa. At first, it seemed like a terrible disaster. Then I realized, I don’t have to clean the basement ever again! It’s all gone. Then I felt a tremendous amount of relief. I realized that the list of things was enough for me; I didn’t need the things themselves.” Anderson’s response surprised me with her ability to emotionally detach from the things themselves (perhaps influenced by her long-standing interest in Buddhism; she also meditates and practices tai chi), and her subsequent choice to focus on the felt and lived experience itself.

Anderson began to theorize deeply about language after this event, a topic that has always interested her. The book let her unravel these questions further than she had before. “I had enough attachment to those things through the words that represented them,” Anderson told me. “In fact,” she continued, “language is all about loss.” To explain further, she fished for an exact quote from the manuscript (and laughed at herself as she did, alternately worried about misquoting herself and the potential pompousness involved). She read: “Language is about loss and, in a way, words are memorials to things and to states. The word ‘yellow’ is a memorial to the color yellow.”

Anderson began to theorize deeply about language after this event, a topic that has always interested her. The book let her unravel these questions further than she had before. “I had enough attachment to those things through the words that represented them,” Anderson told me. “In fact,” she continued, “language is all about loss.” To explain further, she fished for an exact quote from the manuscript (and laughed at herself as she did, alternately worried about misquoting herself and the potential pompousness involved). She read: “Language is about loss and, in a way, words are memorials to things and to states. The word ‘yellow’ is a memorial to the color yellow.”

Portrait of Laurie Anderson by Thilo Hoffmann. Courtesy of the Artist.

In addition to contemplating the semiotic relationships of language, Anderson also considers narrative—the way language gets used, and who stands to benefit from that spin. In a New York Times article, Anderson described herself as a journalist,[ 7] and I asked her to expand upon that label in the context of her role as an artist who tries to capture the world around her. She seemed mildly surprised at first. “I suppose I did say journalist, because in looking at the political situation, I think it’s almost impossible to have a stance because things happen so rapidly and unexpectedly—out of the blue. That constant switching is one of the subjects […] I try to examine.” Following the news means being inundated by the turn of events—there’s always another new, shocking story, then another, and another. While news coverage following breaking stories is not particularly unusual, the swift pace of directing and redirecting the public’s attention from one story to another is its own narrative. For Anderson, the meta-narrative of “constant switching” is cause for alarm, and raises the now-continuous need to ask who (in power) might benefit from sleight-of-hand tactics and media misdirection in the shaping of public opinion.

Our conversation veered sharply into current events: the erroneous missile alert in Hawaii, the narratives surrounding the #MeToo movement and misogyny, Chelsea Manning’s recent announcement that she’s running for Senate, and the tension that comes from living with unstable authority figures. Anderson clarified that she doesn’t hold a “personal gripe” with any one person or administration. She does, however, oppose “ignorance, fearmongering, and sloppiness”—a combination that “entitles people to be mean.” Still, she compared this moment to living with the unhinged captain in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick whose mania “brought the whole ship down.”[ 8] At the same time, she noted, there’s a worrisome sense that no one is actually in charge—which may be even more frightening.

Our conversation veered sharply into current events: the erroneous missile alert in Hawaii, the narratives surrounding the #MeToo movement and misogyny, Chelsea Manning’s recent announcement that she’s running for Senate, and the tension that comes from living with unstable authority figures. Anderson clarified that she doesn’t hold a “personal gripe” with any one person or administration. She does, however, oppose “ignorance, fearmongering, and sloppiness”—a combination that “entitles people to be mean.” Still, she compared this moment to living with the unhinged captain in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick whose mania “brought the whole ship down.”[ 8] At the same time, she noted, there’s a worrisome sense that no one is actually in charge—which may be even more frightening.

Laurie Anderson. All the Things I Lost in the Flood (Rizzoli: New York, 2018). Courtesy of Rizzoli.

“[This moment is] by far the worst disaster I could ever imagine,” Anderson said. “This is an extremely dark time. I do not want to pretend that it looks nicer than it is.” Acknowledging the emergency of our time is in itself an anxiety-producing action, but still another fear of Anderson’s is the dread of not being able to stop something from happening. “I saw a lot of really bad things [happen during my life],” she told me. “But we were always able to do something—to speak up without being shouted down. I’m from a generation where we pride ourselves, for better or worse, on having an influence in having stopped the Vietnam War, and maybe we did, maybe we didn’t. We tried. The efforts of people now are so fractured and short-lived. The Women’s March came and went. What did it really do?”

Among her many other pursuits, Anderson has co-founded a movement calling for January 20 to be an annual “ Art Action Day ,” in an attempt to increase visibility for the arts during a time when already-scarce funding is endangered. As the website states, the founders believe “arts must serve as a catalyst” for social equity. Even without this public proclamation, it’s evident that Anderson views both art and civic participation as indivisible from everyday life, just as she seamlessly shifts in between and across mediums. Clearly, everyday life has an impact on her thoughts about what it means to make art, too: Although we didn’t discuss any specific upcoming projects, during our conversation about seeking the emotional foundation for works, she briefly noted, “And now… I’m not sure which way to direct things. Like you say, it’s so fractured. It could go any direction.” Whichever way she turns next—internally or externally, or toward the poignant spots where the two overlap—and whichever mediums she selects or combines, Anderson is sure to root the work in humanity and connection. Creating art that cultivates empathy is a radical act, if there ever was one.

Among her many other pursuits, Anderson has co-founded a movement calling for January 20 to be an annual “ Art Action Day ,” in an attempt to increase visibility for the arts during a time when already-scarce funding is endangered. As the website states, the founders believe “arts must serve as a catalyst” for social equity. Even without this public proclamation, it’s evident that Anderson views both art and civic participation as indivisible from everyday life, just as she seamlessly shifts in between and across mediums. Clearly, everyday life has an impact on her thoughts about what it means to make art, too: Although we didn’t discuss any specific upcoming projects, during our conversation about seeking the emotional foundation for works, she briefly noted, “And now… I’m not sure which way to direct things. Like you say, it’s so fractured. It could go any direction.” Whichever way she turns next—internally or externally, or toward the poignant spots where the two overlap—and whichever mediums she selects or combines, Anderson is sure to root the work in humanity and connection. Creating art that cultivates empathy is a radical act, if there ever was one.

Notes:

- RoseLee Goldberg, Laurie Anderson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 12.

- Don Shewey, “The Performing Artistry of Laurie Anderson,” New York Times , Feb. 6, 1983, http://www.nytimes.com/1983/02/06/magazine/the-performing-artistry-of-laurie-anderson.html .

- Tess Thackara, “Laurie Anderson Beams a Former Guantanamo Inmate into Manhattan,” Artsy.net , Oct. 1, 2015, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-laurie-anderson-beams-a-former-guantanamo-inmate-into . Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Adam Gabbatt, “Laurie Anderson Plays Concert for Dogs in New York’s Times Square,” The Guardian , Jan. 5, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/jan/05/laurie-anderson-music-dog-concert-times-square-new-york .

- This and all subsequent quotes by Anderson are from a conversation with the author on January 15, 2018.

- Laurie Anderson, “Bring Guantánamo to Park Avenue,” The New Yorker , Sept. 23, 2015, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/bringing-guantanamo-to-park-avenue .

- John Leland, “Laurie Anderson’s Glorious, Chaotic New York,” New York Times , April 21, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/21/nyregion/laurie-anderson-new-york.html .

- In contrast, when Anderson spoke in 1999 of her 98-minute “techno-opera,” Tales and Songs and Stories from ‘Moby Dick’ (1999), her commentary focused on the instruments and multiple narratives, and not on impending national disaster. http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Laurie-Anderson-Hunts-for-Answers-Performance-2899197.php .