Originally published: August 17, 2017

On a hot summer evening, I visited soon-to-be Chicago-based 1 artist Jonas Becker on one of the final days of his residency at Montalvo Arts Center in Saratoga, California. I nervously drove up to the top of a very steep hill and breathed a sigh of relief upon arriving at Becker’s studio, which overlooks the surrounding redwoods. For the past month, he has worked and lived here with his dog Booger, continuing a body of work that has been several years in the making. The series, titled Same Rock (2015–present), takes a variety of formal and tonal approaches—from quiet and subdued sculptures to videos narrated with a sense of corporate optimism. Despite the range in materials and voice, at the project’s center are the beliefs, perceptions, and values of the Appalachian landscape that surround West Virginia, where Becker is originally from. This strategy of producing what Becker calls a “cacophony of visual languages” reveals how authenticity is constructed and shapes our understanding of truth.

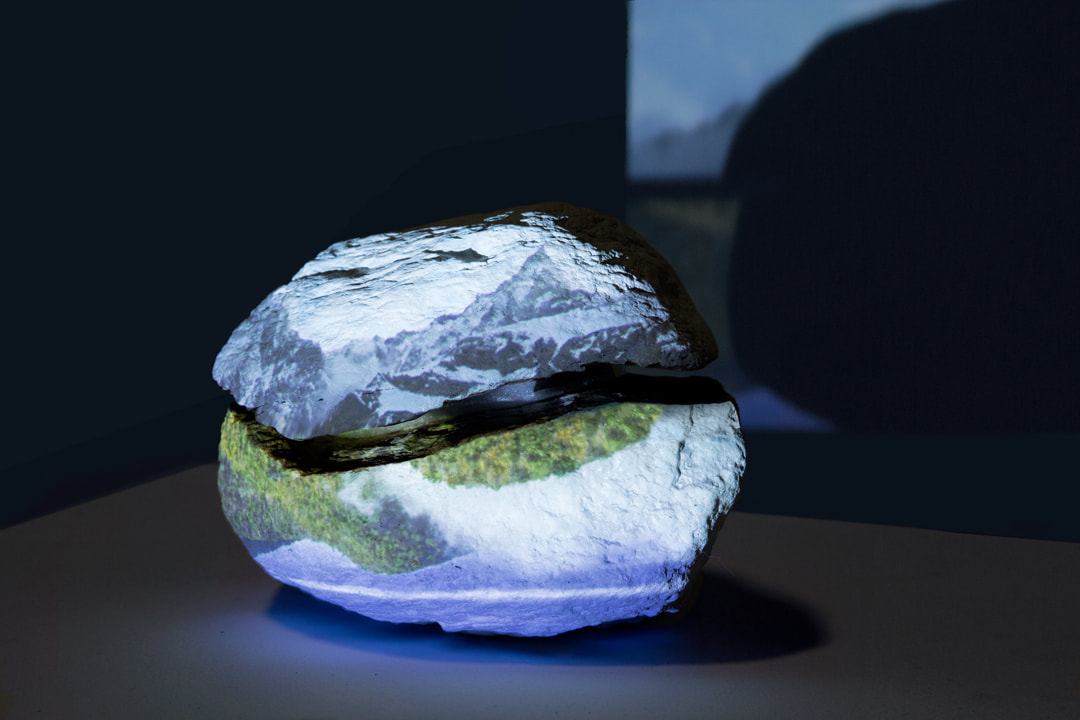

Becker further explores the tension between reality and myth in relationship to the Appalachian environment in the video Holographic Mountain (2017), showing a mountaintop removal (MTR) mining site in Helvetia. MTR is a method of coal mining that involves blasting the top of mountains to retrieve its minerals, thereby leveling the mountain. This decapitation process has an enormous impact on the health of nearby rivers, forests, and residents. 2 It also has an enormous impact on how the mountains are seen and experienced. Here, the mountain is not a refuge or a place for leisurely subliminal exploration. The flattened peaks are surrounded by barren and dry deforestation and filled with the noises of construction. The federal requirements of MTR are such that after a company is finished mining, they are obligated to restore the area with something of “an equal or better economic or public use.” 3 While it sounds promising, in practicality, companies have maneuvered around the requisite by planting a weak field of grass, delaying the completion date of a project, or in one case, proposing the construction of a prison. 4

Becker’s work bridges urban and rural communities and the polarized understandings of landscape—how it is used, experienced, and valued. As a born and bred Californian, I admittedly have given West Virginia little if any passing thought. I don’t have enough knowledge of either its cultural or natural landscape to understand the depth of experiences and concerns the state and its residents face. This lack of understanding undoubtedly has contributed to the larger divide between rural and urban America. Becker’s work offers a bridge, creating a connection through a foundation based on basic human emotions. As Becker and I talk about what it was like growing up in West Virginia, he speaks of a longing for its culture of creating relationships through music and storytelling, rather than political ideology. Storytelling, particularly through tall tales, holds a long tradition in the region.

Tall tales are exaggerated, partially untrue, accounts that are told as truth. They are a part of West Virginian culture—so much so that the state even hosts an annual Liars Contest, in which storytellers are judged on their delivery, confidence, story development, and originality. 5 In a 2006 NPR interview, five-time champion of the Liars Contest, Bil Lepp, talks about the importance of creating stories and using humor to overlook and cope with the hardships faced in the state. He jokes, “If you lie good enough and long enough, eventually the government will hire you.” 6 While probably funny at the time, Lepp’s joke is now jarring in the context of the lies being put forth by the current administration.

It might only be incidental that Trump won by the largest margin in the state of West Virginia during the 2016 election, which so dramatically changed the fabric of America, further dividing rural and urban sentiment. West Virginia was also one out of two states where Trump won in every single county. Just weeks ago, Trump revisited his base to deliver a speech to the Boy Scouts convening in Jamboree, West Virginia. In his now virally shared speech, Trump conveys a story in which the details and facts are both disputable and have changed over time. 7 After all, the importance of a tall tale is not in its truth but in its outcome.

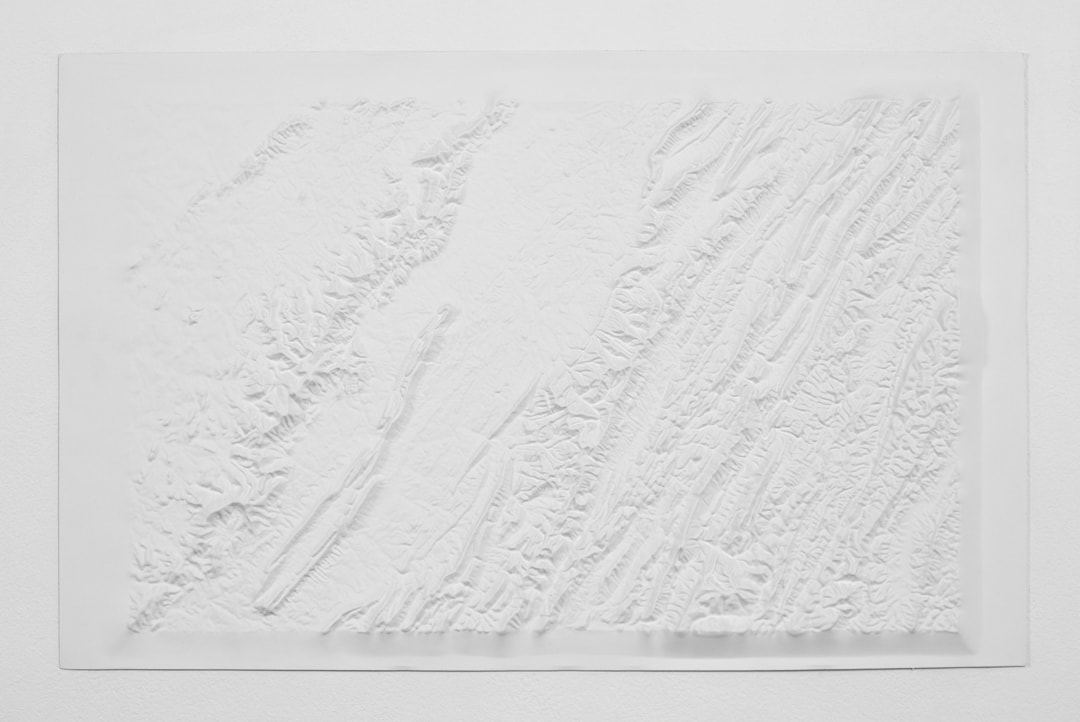

Becker describes his introduction to photography through thinking of the medium as a tall tale. Historically, photography has been understood as a representation of truth, but as Becker suggests, it requires a set up to convey a story. The photographic series Thank G-d for Mississippi (2009) uses the medium’s narrative malleability and is one of Becker’s earliest works focusing on the Appalachian region. As a state, West Virginia faces harsh socioeconomic conditions, falling at the very bottom in areas concerning poverty, healthcare, and education—often ranked 49th in the United States. 8 The title Thank G-d for Mississippi , Becker tells me, alludes to the fact that Mississippi is ranked at 50th. It’s an adage that reflects the sentiment that things could be worse, reflecting the dark humor expressed in West Virginia and how hardships are coped with through language. The series consists of eight large photographs—each at approximately four by five feet—depicting oceans, cliffs, rocky waterbeds, and other sites in the state of West Virginia where people are known to jump—often, to meet their fate. Becker captures these locations by hanging a camera from a boom to retrieve the perspective one would get after having jumped. Their scale enhances the photographs’ askew composition and creates a bodily sense of vertigo. Thank G-d for Mississippi is one of Becker’s early attempts to complicate landscape, revealing that environments are never neutral and hold individual consequences.

NOTES:

1. Beginning in fall 2017, Becker will be an Assistant Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

3. https://www.osmre.gov/lrg/docs/mtpmlureport.pdf .

4. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/rob-perks/mountaintop-removal-reclamation-fail .

http://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/elist/eListRead/doj_withdraws_funding_request

_kentucky_prison_mountaintop-removal/ .

5. http://www.wvculture.org/vandalia/2017/liarscontestsrules2017.pdf .

6. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5435852 .

7. http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2017/07/25/what_was_that_sex_yacht_story

_trump_told_the_boy_scouts.html .